- Home

- Svabhu Kohli

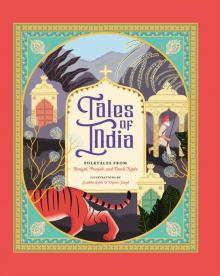

Tales of India

Tales of India Read online

Illustrations by Svabhu Kohli and Viplov Singh, copyright © 2018 by Chronicle Books.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

ISBN: 978-1-4521-6591-2 (hc); 978-1-4521-6675-9 (epub, mobi)

Designed by Emily Dubin and Lizzie Vaughan

Typeset in Adobe Caslon and Ndogk

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

Chronicle books and gifts are available at special quantity discounts to corporations, professional associations, literacy programs, and other organizations. For details and discount information, please contact our premiums department at [email protected] or at 1-800-759-0190.

“‘Delightful creature and most charming princess,’ said she, ‘you have regaled me with an excellent story. But the night is long and tedious. Pray tell me another.’”

— rev. charles swynnerton, f.s.a.,

“Gholâm Badshah and His Son Ghool”

Contents

ANIMAL TALES

The Bear’s Bad Bargain

The Brâhmaṇ Girl That Married a Tiger

The Soothsayer’s Son

The Rat’s Wedding

Gholâm Badshah and His Son Ghool

OUTWITTING AND OUTWITTED

The Ghost-Brahman

Bopolûchî

The Son of Seven Mothers

The Indigent Brahman

The King and the Robbers

The Brahmarâkshasa

LIFE AND DEATH

Life’s Secret

Eesara and Caneesara

The Lord of Death

Prince Lionheart and His Three Friends

The Beggar and the Five Muffins

SOURCES

THE BEAR’S BAD BARGAIN

Punjab

Once upon a time, a very old woodman lived with his very old wife in a tiny hut close to the orchard of a rich man,—so close that the boughs of a pear-tree hung right over the cottage yard. Now it was agreed between the rich man and the woodman, that if any of the fruit fell into the yard, the old couple were to be allowed to eat it; so you may imagine with what hungry eyes they watched the pears ripening, and prayed for a storm of wind, or a flock of flying foxes, or anything which would cause the fruit to fall. But nothing came, and the old wife, who was a grumbling, scolding old thing, declared they would infallibly become beggars. So she took to giving her husband nothing but dry bread to eat, and insisted on his working harder than ever, till the poor old soul got quite thin; and all because the pears would not fall down! At last, the woodman turned round and declared he would not work any more unless his wife gave him khichrî to his dinner; so with a very bad grace the old woman took some rice and pulse, some butter and spices, and began to cook a savoury khichrî. What an appetising smell it had, to be sure! The woodman was for gobbling it up as soon as ever it was ready. “No, no,” cried the greedy old wife, “not till you have brought me in another load of wood; and mind it is a good one. You must work for your dinner.”

So the old man set off to the forest and began to hack and to hew with such a will that he soon had quite a large bundle, and with every faggot he cut he seemed to smell the savoury khichrî and think of the feast that was coming.

Just then a bear came swinging by, with its great black nose tilted in the air, and its little keen eyes peering about; for bears, though good enough fellows on the whole, are just dreadfully inquisitive.

“Peace be with you, friend!” said the bear, “and what may you be going to do with that remarkably large bundle of wood?”

“It is for my wife,” returned the woodman. “The fact is,” he added confidentially, smacking his lips, “she has made such a khichrî for dinner! and if I bring in a good bundle of wood she is pretty sure to give me a plentiful portion. Oh, my dear fellow, you should just smell that khichrî!”

At this the bear’s mouth began to water, for, like all bears, he was a dreadful glutton.

“Do you think your wife would give me some too, if I brought her a bundle of wood?” he asked anxiously.

“Perhaps; if it was a very big load,” answered the woodman craftily.

“Would—would four hundredweight be enough?” asked the bear.

“I’m afraid not,” returned the woodman, shaking his head; “you see khichrî is an expensive dish to make,—there is rice in it, and plenty of butter, and pulse, and—”

“Would—would eight hundredweight do?”

“Say half a ton, and it’s a bargain!” quoth the woodman.

“Half a ton is a large quantity!” sighed the bear.

“There is saffron in the khichrî,” remarked the woodman casually.

The bear licked his lips, and his little eyes twinkled with greed and delight.

“Well, it’s a bargain! Go home sharp and tell your wife to keep the khichrî hot; I’ll be with you in a trice.”

Away went the woodman in great glee to tell his wife how the bear had agreed to bring half a ton of wood in return for a share of the khichrî.

Now the wife could not help allowing that her husband had made a good bargain, but being by nature a grumbler, she was determined not to be pleased, so she began to scold the old man for not having settled exactly the share the bear was to have; “For,” said she, “he will gobble up the potful before we have finished our first helping.”

On this the woodman became quite pale. “In that case,” he said, “we had better begin now, and have a fair start.” So without more ado they squatted down on the floor, with the brass pot full of khichrî between them, and began to eat as fast as they could.

“Remember to leave some for the bear, wife,” said the woodman, speaking with his mouth crammed full.

“Certainly, certainly,” she replied, helping herself to another handful.

“My dear,” cried the old woman in her turn, with her mouth so full that she could hardly speak, “remember the poor bear!”

“Certainly, certainly, my love!” returned the old man, taking another mouthful.

So it went on, till there was not a single grain left in the pot.

“What’s to be done now?” said the woodman; “it is all your fault, wife, for eating so much.”

“My fault!” retorted his wife scornfully, “why, you ate twice as much as I did!”

“No, I didn’t!”

“Yes, you did!—men always eat more than women.”

“No, they don’t!”

“Yes, they do!”

“Well, it’s no use quarrelling about it now,” said the woodman, “the khichrî’s gone, and the bear will be furious.”

“That wouldn’t matter much if we could get the wood,” said the greedy old woman. “I’ll tell you what we must do,—we must lock up everything there is to eat in the house, leave the khichrî pot by the fire, and hide in the garret. When the bear comes he will think we have gone out and left his dinner for him. Then he will throw down his bundle and come in. Of course he will rampage a little when he finds the pot is empty, but he can’t do much mischief, and I don’t think he will take the trouble of carrying the wood away.”

So they made haste to lock up all the food and hide themselves in the garret.

Meanwhile the bear had been toiling and moiling away at his bundle of wood, which took him much longer to collect than he expected; however, at last he arrived quite exhausted at the woodcutter’s cottage. Seeing the brass khichrî pot by the fire, he threw down his load and went in. And then—mercy! wasn’t he angry when he found nothing in it—not even a grain of rice, nor a tiny wee

bit of pulse, but only a smell that was so uncommonly nice that he actually cried with rage and disappointment. He flew into the most dreadful temper, but though he turned the house topsy-turvy, he could not find a morsel of food. Finally, he declared he would take the wood away again, but, as the crafty old woman had imagined, when he came to the task, he did not care, even for the sake of revenge, to carry so heavy a burden.

“I won’t go away empty-handed,” said he to himself, seizing the khichrî pot; “if I can’t get the taste I’ll have the smell!”

Now, as he left the cottage, he caught sight of the beautiful golden pears hanging over into the yard. His mouth began to water at once, for he was desperately hungry, and the pears were the first of the season; in a trice he was on the wall, up the tree, and, gathering the biggest and ripest one he could find, was just putting it into his mouth, when a thought struck him.

“If I take these pears home I shall be able to sell them for ever so much to the other bears, and then with the money I shall be able to buy some khichrî. Ha, ha! I shall have the best of the bargain after all!”

So saying, he began to gather the ripe pears as fast as he could and put them into the khichrî pot, but whenever he came to an unripe one he would shake his head and say, “No one would buy that, yet it is a pity to waste it.” So he would pop it into his mouth and eat it, making wry faces if it was very sour.

Now all this time the woodman’s wife had been watching the bear through a crevice, and holding her breath for fear of discovery; but, at last, what with being asthmatic, and having a cold in her head, she could hold it no longer, and just as the khichrî pot was quite full of golden ripe pears, out she came with the most tremendous sneeze you ever heard—“A-h-che-u !”

The bear, thinking some one had fired a gun at him, dropped the khichrî pot into the cottage yard, and fled into the forest as fast as his legs would carry him.

So the woodman and his wife got the khichrî, the wood, and the coveted pears, but the poor bear got nothing but a very bad stomach-ache from eating unripe fruit.

THE BRHMAṆ GIRL THAT MARRIED a TIGER

Tamil Nadu

In a certain village there lived an old Brâhmaṇ who had three sons and a daughter. The girl being the youngest was brought up most tenderly and became spoilt, and so whenever she saw a beautiful boy she would say to her parents that she must be wedded to him. Her parents were, therefore, much put about to devise excuses for taking her away from her youthful lovers. Thus passed on some years, till the girl was very near attaining her puberty and then the parents, fearing that they would be driven out of their caste if they failed to dispose of her hand in marriage before she came to the years of maturity, began to be eager about finding a bridegroom for her.

Now near their village there lived a fierce tiger, that had attained to great proficiency in the art of magic, and had the power of assuming different forms. Having a great taste for Brâhmaṇ’s food, the tiger used now and then to frequent temples and other places of public feeding in the shape of an old famished Brâhmaṇ in order to share the food prepared for the Brâhmaṇs. The tiger also wanted, if possible, a Brâhmaṇ wife to take to the woods, and there to make her cook his meals after her fashion. One day when he was partaking of his meals in Brâhmaṇ shape at a satra1, he heard the talk about the Brâhmaṇ girl who was always falling in love with every beautiful Brâhmaṇ boy. Said he to himself, “Praised be the face that I saw first this morning. I shall assume the shape of a Brâhmaṇ boy, and appear as beautiful as beautiful can be, and win the heart of the girl.”

Next morning he accordingly became in form a great Śâstrin (proficient in the Râmâyaṇa) and took his seat near the ghâṭ of the sacred river of the village. Scattering holy ashes profusely over his body he opened the Râmâyaṇa and began to read.

“The voice of the new Śâstrin is most enchanting. Let us go and hear him,” said some women among themselves, and sat down before him to hear him expound the great book. The girl for whom the tiger had assumed this shape came in due time to bathe at the river, and as soon as she saw the new Śâstrin fell in love with him, and bothered her old mother to speak to her father about him, so as not to lose her new lover. The old woman too was delighted at the bridegroom whom fortune had thrown in her way, and ran home to her husband, who, when he came and saw the Śâstrin, raised up his hands in praise of the great god Mahêśvara. The Śâstrin was now invited to take his meals with them, and as he had come with the express intention of marrying the daughter he, of course, agreed.

A grand dinner followed in honour of the Śâstrin, and his host began to question him as to his parentage, &c., to which the cunning tiger replied that he was born in a village beyond the adjacent wood. The Brâhmaṇ had no time to wait for better enquiry, and as the boy was very fair he married his daughter to him the very next day. Feasts followed for a month, during which time the bridegroom gave every satisfaction to his new relatives, who supposed him to be human all the while. He also did full justice to the Brâhmaṇic dishes, and gorged everything that was placed before him.

After the first month was over the tiger-bridegroom bethought him of his accustomed prey, and hankered after his abode in the woods. A change of diet for a day or two is all very well, but to renounce his own proper food for more than a month was hard. So one day he said to his father-in-law, “I must go back soon to my old parents, for they will be pining at my absence. But why should we have to bear the double expense of my coming all the way here again to take my wife to my village? So if you will kindly let me take the girl with me I shall take her to her future home, and hand her over to her mother-in-law, and see that she is well taken care of.” The old Brâhmaṇ agreed to this, and replied, “My dear son-in-law, you are her husband and she is yours and we now send her with you, though it is like sending her into the wilderness with her eyes tied up. But as we take you to be everything to her, we trust you to treat her kindly.” The mother of the bride shed tears at the idea of having to send her away, but nevertheless the very next day was fixed for the journey. The old woman spent the whole day in preparing cakes and sweetmeats for her daughter, and when the time for the journey arrived, she took care to place in her bundles and on her head one or two margosa2 leaves to keep off demons. The relatives of the bride requested her husband to allow her to rest wherever she found shade, and to eat wherever she found water, and to this he agreed, and so they began their journey.

The boy tiger and his human wife pursued their journey for two or three ghaṭikâs3 in free and pleasant conversation, when the girl happened to see a fine pond, round which the birds were warbling their sweet notes. She requested her husband to follow her to the water’s edge and to partake of some of the cakes and sweetmeats with her. But he replied, “Be quiet, or I shall show you my original shape.” This made her afraid, so she pursued her journey in silence until she saw another pond, when she asked the same question of her husband, who replied in the same tone. Now she was very hungry, and not liking her husband’s tone, which she found had greatly changed ever since they had entered the woods, said to him, “Show me your original shape.”

No sooner were these words uttered than her husband remained no longer a man. Four legs, a striped skin, a long tail and a tiger’s face came over him suddenly and, horror of horrors! a tiger and not a man stood before her! Nor were her fears stilled when the tiger in human voice began as follows:—“Know henceforth that I, your husband, am a tiger—this very tiger that now speaks to you. If you have any regard for your life you must obey all my orders implicitly, for I can speak to you in human voice and understand what you say. In a couple of ghaṭikâs we shall reach my home, of which you will become the mistress. In the front of my house you will see half a dozen tubs, each of which you must fill up daily with some dish or other cooked in your own way. I shall take care to supply you with all the provisions you want.” So saying the tiger slowly conducted her to his house.

The misery of the girl may more be i

magined than described, for if she were to object she would be put to death. So, weeping all the way, she reached her husband’s house. Leaving her there he went out and returned with several pumpkins and some flesh, of which she soon prepared a curry and gave it to her husband. He went out again after this and returned in the evening with several vegetables and some more flesh and gave her an order:—“Every morning I shall go out in search of provisions and prey and bring something with me on my return: you must keep cooked for me whatever I leave in the house.”

Next morning as soon as the tiger had gone away she cooked everything left in the house and filled all the tubs with food. At the 10th ghaṭikâ the tiger returned and growled out, “I smell a man! I smell a woman in my wood.” And his wife for very fear shut herself up in the house. As soon as the tiger had satisfied his appetite he told her to open the door, which she did, and they talked together for a time, after which the tiger rested awhile, and then went out hunting again. Thus passed many a day, till the tiger’s Brâhmaṇ wife had a son, which also turned out to be only a tiger.

One day, after the tiger had gone out to the woods, his wife was crying all alone in the house, when a crow happened to peck at some rice that was scattered near her, and seeing the girl crying, began to shed tears.

“Can you assist me?” asked the girl.

“Yes,” said the crow.

So she brought out a palmyra leaf and wrote on it with an iron nail all her sufferings in the wood, and requested her brothers to come and relieve her. This palmyra leaf she tied to the neck of the crow, which, seeming to understand her thoughts, flew to her village and sat down before one of her brothers. He untied the leaf and read the contents of the letter and told them to his other brothers. All the three then started for the wood, asking their mother to give them something to eat on the way. She had not enough of rice for the three, so she made a big ball of clay and stuck it over with what rice she had, so as to make it look like a ball of rice. This she gave to the brothers to eat on their way and started them off to the woods.

Tales of India

Tales of India