- Home

- Svabhu Kohli

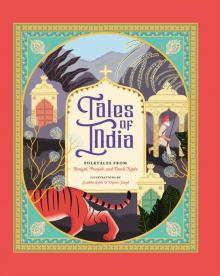

Tales of India Page 3

Tales of India Read online

Page 3

How came a crown in the jaws of a tiger? It is not a difficult question to solve. A king must have furnished the table of the tiger for a day or two. Had it not been for that, the tiger could not have had a crown with him. Even so it was. The king of Ujjaini had a week before gone with all his hunters on a hunting expedition. All on a sudden a tiger—as we know now, the very tiger-king himself—started from the wood, seized the king, and vanished. The hunters returned and informed the prince about the sad calamity that had befallen his father. They all saw the tiger carrying away the king. Yet such was their courage that they could not lift their weapons to bring to the prince the corpse at least of his father; their courage reminds us of the couplet in the Child’s Story:—

“Four and twenty sailors went to kill a snail;

The best man among them dares not touch her tail.”

When they informed the prince about the death of his father he wept and wailed, and gave notice that he would give half of his kingdom to any one who should bring him news about the murderer of his father. The prince did not at all believe that his father was devoured by the tiger. His belief was that some hunters, coveting the ornaments on the king’s person, had murdered him. Hence he had issued the notice. The goldsmith knew full well that it was a tiger that killed the king, and not any hunter’s hands, since he had heard from Gaṅgâdhara about how he obtained the crown. Still, ambition to get half the kingdom prevailed, and he resolved with himself to make over Gaṅgâdhara as the king’s murderer. The crown was lying on the floor where Gaṅgâdhara left it with his full confidence in Mâṇikkâśâri. Before his protector’s return the goldsmith, hiding the crown under his garments, flies to the palace. He went before the prince and informed him that the assassin was caught, and placed the crown before him. The prince took it into his hands, examined it, and at once gave half the kingdom to Mâṇikkâśâri, and then enquired about the murderer. He is bathing in the river, and is of such and such appearance, was the reply. At once four armed soldiers fly to the river, and bind hand and foot the poor Brâhmaṇ, who sits in meditation, without any knowledge of the fate that hangs over him. They brought Gaṅgâdhara to the presence of the prince, who turned his face away from the murderer or supposed murderer, and asked his soldiers to throw him into the kârâgṛiham. In a minute, without knowing the cause, the poor Brâhmaṇ found himself in the dark caves of the kârâgṛiham.

In old times the kârâgṛiham answered the purposes of the modern jail. It was a dark cellar underground, built with strong stone walls, into which any criminal guilty of a capital offence was ushered to breathe his last there without food and drink. Into such a cellar Gaṅgâdhara was pushed down. In a few hours after he left the goldsmith he found himself inside a dark cell stinking with human bodies, dying and dead. What were his thoughts when he reached that place? “It is the goldsmith that has brought me to this wretched state; and, as for the prince: Why should he not enquire as to how I obtained the crown? It is of no use to accuse either the goldsmith or the prince now. We are all the children of fate. We must obey her commands. Daśa-varshâṇi bandhanam. This is but the first day of my father’s prophecy. So far his statement is true. But how am I going to pass ten years here? Perhaps without anything to keep up my life I may drag on my existence for a day or two. But how to pass ten years? That cannot be, and I must die. Before death comes let me think of my faithful brute friends.”

So pondered Gaṅgâdhara in the dark cell underground, and at that moment thought of his three friends. The tiger-king, serpent-king, and rat-king assembled at once with their armies at a garden near the kârâgṛiham, and for a while did not know what to do. A common cause—how to reach their protector who was now in the dark cell underneath—united them all. They held their council, and decided to make an underground passage from the inside of a ruined well to the kârâgṛiham. The rat râja issued an order at once to that effect to his army. They with their nimble teeth bored the ground a long way to the walls of the prison. After reaching it they found that their teeth could not work on the hard stones. The bandicoots were then specially ordered for the business, they with their hard teeth made a small slit in the wall for a rat to pass and repass without difficulty. Thus a passage was effected.

The rat râja entered first to condole with his protector for his calamity. The king of the tigers sent word through the snake-king that he sympathised most sincerely with his sorrow, and that he was ready to render all help for his deliverance. He suggested a means for his escape also. The serpent râja went in, and gave Gaṅgâdhara hopes of delivery. The rat king undertook to supply his protector with provisions. “Whatever sweetmeats or bread are prepared in any house, one and all of you must try to bring whatever you can to our benefactor. Whatever clothes you find hanging in a house, cut down, dip the pieces in water and bring the wet bits to our benefactor. He will squeeze them and gather water for drink; and the bread and sweetmeats shall form his food.” Thus ordered the king of the rats, and took leave of Gaṅgâdhara. They in obedience to their king’s order continued to supply provisions and water.

The Nâgarâja said:—“I sincerely condole with you in your calamity; the tiger-king also fully sympathises with you, and wants me to tell you so, as he cannot drag his huge body here as we have done with our small ones. The king of the rats has promised to do his best to keep up your life. We would now do what we can for your release. From this day we shall issue orders to our armies to oppress all the subjects of this kingdom. The percentage of death by snake-bite and tigers shall increase from this day. And day by day it shall continue to increase till your release. After eating what the rats bring you you had better take your seat near the entrance of the kârâgṛiham. Owing to the several unnatural deaths some people that walk over the prison might say, ‘How unjust the king has turned out now. Were it not for his injustice such early deaths by snake-bite could never occur.’ Whenever you hear people speaking so, you had better bawl out so as to be heard by them, ‘The wretched prince imprisoned me on the false charge of having killed his father, while it was a tiger that killed him. From that day these calamities have broken out in his dominions. If I were released I would save all by my powers of healing poisonous wounds and by incantations.’ Some one may report this to the king, and if he knows it, you will obtain your liberty.” Thus comforting his protector in trouble, he advised him to pluck up courage, and took leave of him. From that day tigers and serpents, acting under the special orders of their kings, united in killing as many persons and cattle as possible. Every day people were being carried away by tigers or bitten by serpents. This havoc continued. Gaṅgâdhara was roaring as loud as he could that he would save those lives, had he only his liberty. Few heard him. The few that did took his words for the voice of a ghost. “How could he manage to live without food and drink for so long a time?” said the persons walking over his head to each other. Thus passed on months and years. Gaṅgâdhara sat in the dark cellar, without the sun’s light falling upon him, and feasted upon the bread-crumbs and sweetmeats that the rats so kindly supplied him with. These circumstances had completely changed his body. He had become a red, stout, huge, unwieldy lump of flesh. Thus passed full ten years, as prophesied in the horoscope—Daś a-varshâṇi bandhanam.

Ten complete years rolled away in close imprisonment. On the last evening of the tenth year one of the serpents got into the bed-chamber of the princess and sucked her life. She breathed her last. She was the only daughter of the king. He had no other issue—son or daughter. His only hope was in her; and she was snatched away by a cruel and untimely death. The king at once sent for all the snake-bite curers. He promised half his kingdom, and his daughter’s hand to him who would restore her to life. Now it was that a servant of the king who had several times overheard Gaṅgâdhara’s exclamation reported the matter to him. The king at once ordered the cell to be examined. There was the man sitting in it. How has he managed to live so long in the cell? Some whispered that he must be a divine being. Som

e concluded that he must surely win the hand of the princess by restoring her to life. Thus they discussed and the discussions brought Gaṅgâdhara to the king.

The king no sooner saw Gaṅgâdhara than he fell on the ground. He was struck by the majesty and grandeur of his person. His ten years’ imprisonment in the deep cell underground had given a sort of lustre to his body, which was not to be met with in ordinary persons. His hair had first to be cut before his face could be seen. The king begged forgiveness for his former fault, and requested him to revive his daughter.

“Bring me in a muhûrta all the corpses of men and cattle dying and dead, that remain unburnt or unburied within the range of your dominions; I shall revive them all:” were the only words that Gaṅgâdhara spoke. After it he closed his lips as if in deep meditation, which commanded him more respect in the company.

Cart-loads of corpses of men and cattle began to come in every minute. Even graves, it is said, were broken open, and corpses buried a day or two before were taken out and sent for the revival. As soon as all were ready Gaṅgâdhara took a vessel full of water and sprinkled it over them all, thinking upon his Nâgarâja and Vyâghrarâja. All rose up as if from deep slumber, and went to their respective homes. The princess, too, was restored to life. The joy of the king knows no bounds. He curses the day on which he imprisoned him, accuses himself for having believed the word of a goldsmith, and offers him the hand of his daughter and the whole kingdom, instead of half as he promised. Gaṅgâdhara would not accept anything. The king requested him to put a stop for ever to those calamities. He agreed to do so, and asked the king to assemble all his subjects in a wood near the town. “I shall there call in all the tigers and serpents and give them a general order.” So said Gaṅgâdhara, and the king accordingly gave the order. In a couple of ghaṭikas the wood near Ujjaini was full of people who assembled to witness the authority of man over such enemies of human beings as tigers and serpents. “He is no man; be sure of that. How could he have managed to live for ten years without food and drink? He is surely a god.” Thus speculated the mob.

When the whole town was assembled just at the dusk of evening, Gaṅgâdhara sat dumb for a moment and thought upon the Vyâghrarâja and Nâgarâja, who came running with all their armies. People began to take to their heels at the sight of the tigers. Gaṅgâdhara assured them of safety, and stopped them.

The grey light of the evening, the pumpkin colour of Gaṅgâdhara, the holy ashes scattered lavishly over his body, the tigers and snakes humbling themselves at his feet, gave him the true majesty of the god Gaṅgâdhara. For who else by a single word could thus command vast armies of tigers and serpents, said some among the people. “Care not for it; it may be by magic. That is not a great thing. That he revived cart-loads of corpses makes him surely Gaṅgâdhara,” said others. The scene produced a very great effect upon the minds of the mob.

“Why should you, my children, thus trouble these poor subjects of Ujjaini? Reply to me, and henceforth desist from your ravages.” Thus said the Soothsayer’s son, and the following reply came from the king of the tigers; “Why should this base king imprison your honour, believing the mere word of a goldsmith that your honour killed his father? All the hunters told him that his father was carried away by a tiger. I was the messenger of death sent to deal the blow on his neck. I did it, and gave the crown to your honour. The prince makes no enquiry, and at once imprisons your honour. How can we expect justice from such a stupid king as that. Unless he adopts a better standard of justice we will go on with our destruction.”

The king heard, cursed the day on which he believed in the word of the goldsmith, beat his head, tore his hair, wept and wailed for his crime, asked a thousand pardons, and swore to rule in a just way from that day. The serpent-king and the tiger-king also promised to observe their oath as long as justice prevailed, and took their leave. The goldsmith fled for his life. He was caught by the soldiers of the king, and was pardoned by the generous Gaṅgâdhara, whose voice now reigned supreme. All returned to their homes.

The king again pressed Gaṅgâdhara to accept the hand of his daughter. He agreed to do so, not then, but some time afterwards. He wished to go and see his elder brother first, and then to return and marry the princess. The king agreed; and Gaṅgâdhara left the city that very day on his way home.

It so happened that unwittingly he took a wrong road, and had to pass near a sea coast. His elder brother was also on his way up to Bânâras by that very same route. They met and recognised each other, even at a distance. They flew into each other’s arms. Both remained still for a time without knowing anything. The emotion of pleasure (ânanda) was so great, especially in Gaṅgâdhara, that it proved dangerous to his life. In a word, he died of joy.

The sorrow of the elder brother could better be imagined than described. He saw again his lost brother, after having given up, as it were, all hopes of meeting him. He had not even asked him his adventures. That he should be snatched away by the cruel hand of death seemed unbearable to him. He wept and wailed, took the corpse on his lap, sat under a tree, and wetted it with tears. But there was no hope of his dead brother coming to life again.

The elder brother was a devout worshipper of Gaṇapati. That was a Friday, a day very sacred to that god. The elder brother took the corpse to the nearest Gaṇêśa temple and called upon him. The god came, and asked him what he wanted. “My poor brother is dead and gone; and this is his corpse. Kindly keep it under your charge till I finish your worship. If I leave it anywhere else the devils may snatch it away when I am absent in your worship; after finishing your pûjâ I shall burn him.” Thus said the elder brother, and giving the corpse to the god Gaṇêśa he went to prepare himself for that deity’s worship. Gaṇêśa made over the corpse to his Gaṇas, asking them to watch over it carefully.

So receives a spoiled child a fruit from its father, who, when he gives it the fruit asks the child to keep it safe. The child thinks within itself, “Papa will excuse me if I eat a portion of it.” So saying it eats a portion, and when it finds it so sweet, it eats the whole, saying, “Come what will, what will papa do, after all, if I eat it? Perhaps give me a stroke or two on the back. Perhaps he may excuse me.” In the same way these Gaṇas of Gaṇapati first ate a portion of the corpse, and when they found it sweet, for we know that it was crammed up with the sweetmeats of the kind rats, devoured the whole, and were consulting about offering the best excuse possible to their master.

The elder brother, after finishing the pûjâ, demanded from the god his brother’s corpse. The belly-god called his Gaṇas, who came to the front blinking, and fearing the anger of their master. The god was greatly enraged. The elder brother was highly vexed. When the corpse was not forthcoming he cuttingly remarked, “Is this, after all, the return for my deep belief in you? You are unable even to return my brother’s corpse.” Gaṇêśa was much ashamed at the remark, and at the uneasiness that he had caused to his worshipper, so he by his divine power gave him a living Gaṅgâdhara instead of the dead corpse. Thus was the second son of the Soothsayer restored to life.

The brothers had a long talk about each other’s adventures. They both went to Ujjaini, where Gaṅgâdhara married the princess, and succeeded to the throne of that kingdom. He reigned for a long time, conferring several benefits upon his brother. How is the horoscope to be interpreted? A special synod of Soothsayers was held. A thousand emendations were suggested. Gaṅgâdhara would not accept them. At last one Soothsayer cut the knot by stopping at a different place in reading, “Samudratîrê maraṇam kiñchit.” “On the sea shore death for some time. Then Bhôgaṁ bhavishyati. There shall be happiness for the person concerned.” Thus the passage was interpreted. “Yes; my father’s words never went wrong,” said Gaṅgâdhara. The three brute kings continued their visits often to the Soothsayer’s son, the then king of Ujjaini. Even the faithless goldsmith became a frequent visitor at the palace, and a receiver of several benefits from the royal hands.

THE R

AT’S WEDDING

Punjab

Once upon a time a fat sleek Rat was caught in a shower of rain, and being far from shelter he set to work and soon dug a nice hole in the ground, in which he sat as dry as a bone while the raindrops splashed outside, making little puddles on the road.

Now in the course of his digging he came upon a fine bit of root, quite dry and fit for fuel, which he set aside carefully—for the Rat is an economical creature—in order to take it home with him. So when the shower was over, he set off with the dry root in his mouth. As he went along, daintily picking his way through the puddles, he saw a poor man vainly trying to light a fire, while a little circle of children stood by, and cried piteously.

Tales of India

Tales of India